The Cobalt Uncertainty: how does deep sea mining affect the supply chain?

Cobalt is a silvery-gray metal with a faint bluish tint that plays an outsized role in modern technology, powering everything from electric vehicle batteries to aeroplanes. How does the plan to extract it from the ocean impact a delicately balanced supply chain?

Cobalt takes centre stage internationally on Wednesday when the yearly Cobalt Congress convenes to discuss the state of play for this metal.

Normally concerned with terrestrial supply, this year's meeting of industry players in Singapore, hosted by The Cobalt Institute, will no doubt take stock of Donald Trump's deep sea mining executive order and what it might mean for supply markets.

Last May in New York, as they discussed runaway oversupply, falling prices, and evolving demand, the geopolitical landscape could not have looked more different.

Joe Biden was still in office and his Inflation Reduction Act was the main policy concern from the American standpoint.

The Conservatives in the UK had not yet been booted from office by Keir Starmer's Labour and the advance of net-zero-skeptical right wing parties in the EU parliament had not yet materialised.

But a year is a long time.

Since they last had genteel fireside chats where consultants reassured that demand for cobalt would catch up with the oversupply, Americans have elected a president obsessed with metals like cobalt. One, who has been nothing short of desperate to overcome the China problem.

The geopolitics of it all

China overwhelmingly dominates both the global supply chain for raw and refined minerals, which we discussed in this piece, as well as the production of end user applications like EV batteries.

There's also the small business of a trade war between China and the United States, with tit-for-tat tariffs, export controls on critical minerals by China, and crucially of interest to Deep Blue League and its readers, Trump's explosive deep sea mining executive order.

The order calls for the US to press ahead without international regulatory approval to mine cobalt - among other metals - from the Pacific Ocean floor. Canadian Miner, The Metals Company (TMC), has already submitted an application, through its US subsidiary, for a licence and says it plans to start exploitation by 2027.

Cobalt Congress 2024 had acknowledged the political risk in a year chock full of elections, but the needle had been set at moderate.

Next week, it will be interesting to test the temperature among industry traders, market analysts and policy wonks and observe how much potential deep sea supply is factored into forward looking models.

After all, cobalt on the ocean floor is said to exceed land reserves by magnitudes, and the 2 million tonnes in TMC's line of site outstrips 2024's production by 1.7 million.

TMC boasted to investors in March that deep sea cobalt was enough to meet American demand for 165 years.

And since terrestrial supply is concentrated in two main countries, Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia, the idea of operating offshore without the pesky problem of humans, may be seen as a huge comparative advantage.

There's no immediately apparent environmental toll that can be seen with the naked eye or media lenses, no conflicts to contend with like the DRC, no artisanal producers to be concerned with from an ESG perspective.

So what's happening in the terrestrial market?

Well, for one, lots and lots of cobalt production. Production grew by 30 percent in 2024, and by 23 percent in 2023. By contrast, demand has not kept pace, lagging by 21% last year.

That put downward pressure on prices which are now at near ten-year lows.

In 2018, cobalt suppliers were riding high, reeling in USD$40 per pound or $80, 000 per tonne, as EVs became increasingly popular.

Today, they're copping a measly USD$11 per pound or $24,300 per tonne as usage slows down, cobalt free battery chemistries gain popularity in China, and the world's largest producer, China's CMOC Group, is said to be strategically flooding the market to maintain market share and crowd out western competition.

Why is cobalt demand lagging?

It's mostly about electric vehicles or EVs. It's hard to talk about cobalt without talking about EVs.

For years, cobalt has been a critical ingredient in the lithium-ion batteries that drive electrification of transportation and other market applications like jet engines and consumer electronics.

It makes these batteries stable, gives them longevity, and packs a lot of energy, which gives EVs the range they need to appeal to car drivers.

Switching from traditional cars to EVs is a key plank of the transition towards a low carbon economy, a key ambition for the entire globe this century as countries move at varying speeds towards net zero.

There are over a billion traditional cars and vans in the world and they, along with other forms of transportation, contribute over 30% of global gas emissions. So getting rid of them at pace is a key policy objective of most developed countries and on the medium to longer term agenda of developing ones.

Apart from cobalt's role in the electrification of vehicles, it is also infinitely recyclable, which has made it even more valuable from a sustainable energy standpoint.

So for cobalt suppliers, EV production is the best game in town, accounting for 45% of market demand. Battery applications in general account for a whopping 73 percent of the demand for cobalt. And nearly all demand growth comes from these areas.

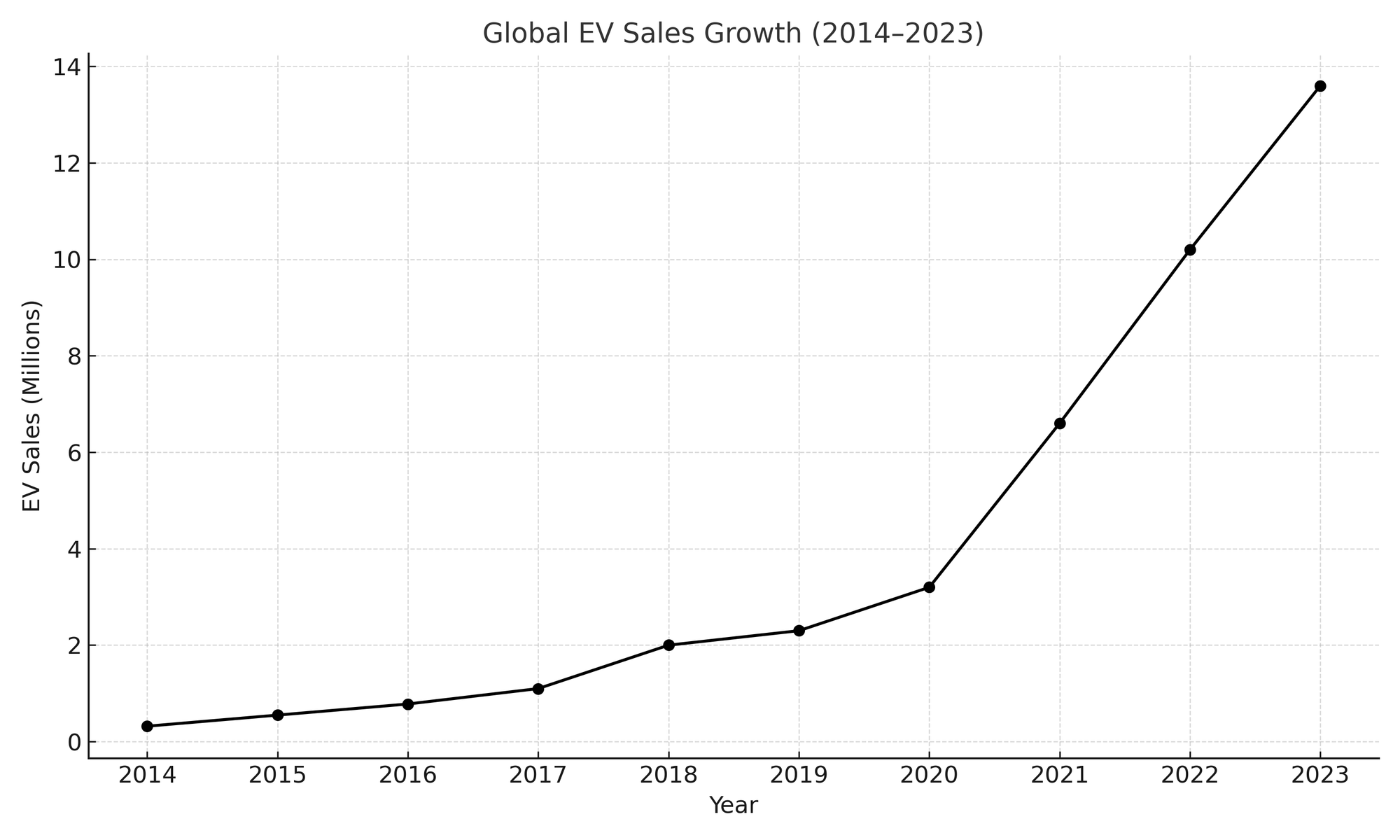

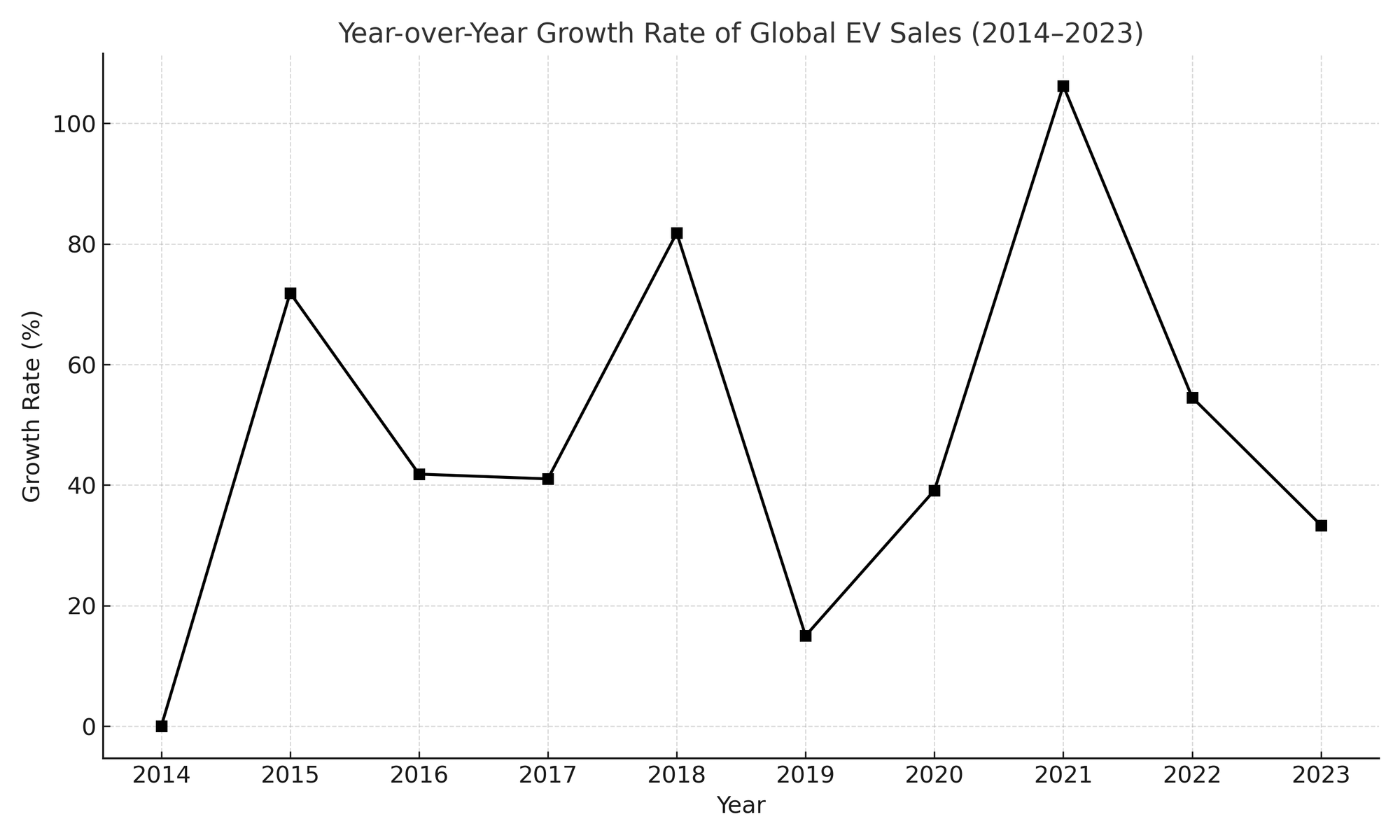

But the rate of EV sales has slowed. It's still gaining market share relative to traditional vehicles, but the pace is less frenetic.

Charging infrastructure has not kept pace and people aren't buying EVs as fast as they once did a few years back (see second graph below), although absolute numbers and market share continue to go up (first graph).

Cobalt has competition

Cobalt is also no longer the only game in town for battery chemistry. Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries are now an alternative, being increasingly used by China, which produces two-thirds of all new electric vehicles.

LFP is cheaper and not fraught with the same problems in its supply chain as cobalt is.

To add to the pressures, the EU now requires companies to conduct risk assessments of their entire supply chain and take action if ESG issues are identified. Not doing so could result in financial blocks.

Back to Deep Sea Mining

The two fold argument of pricing and battery alternatives is why deep sea mining conservationists have been hitting the financial viability argument hard.

They know it’s an uphill battle to win an environmental argument against economics, so the market fundamentals are a gift.

In a US Congress hearing end of April, the global coalition group that managed to get 32 countries to agree on a moratorium against deep sea mining, pressed the argument and were joined by a few US lawmakers.

The group, The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, last month published a report which includes a chapter on The Economics of a Moratorium. The report was the subject of our deep dive last week.

Of the four main metals to be mined from the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean - lithium, manganese, nickel and cobalt - prices have been falling.

But The Metals Company which is getting ready to set up shop on the Pacific Ocean seabed said it wasn't worried about the financials and that the argument was just a "tactic" of detractors.

And Impossible Metals, another company which has applied for a US licence (but within US territorial limits off the coast of American Samoa) says they can do everything ten times cheaper than terrestrial miners and that lower prices will actually help to innoculate them from the effects of Chinese dumping tactics.

Impossible Metals, founder-led by Oliver Gunasekara, also says it's not intimidated by LFP's fast moving market share.

Will the market stay depressed?

Market analysts at last year's Congress back up the prospectors. Harry Fisher a senior consultant at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, told conference goers that demand would catch up and rebalance the state of play in the medium term.

He said LFP preference was mostly restricted to the Chinese EV market, and that cobalt will continue to be valued in batteries globally because of its superior energy density.

Fisher also argued that cobalt containing batteries had growth potential in terms of their energy capacity, but that LFP technology had peaked.

As the transition towards net zero continues and reaches a milestone in 2030, EV battery demand for cobalt is expected to grow from 45% to 68% and overall battery applications will grow to 95% by 2030.

Use of cobalt in defence manufacturing and aeronautics will also increase year on year, according to the analysis, and together, these drivers of demand are expected to rebalance the market.

Cobalt Congress 2025

It remains to be seen how the potential imminence of deep sea mining will affect that outlook or whether it will even register a blip on the radar among cobalt interests.

Cobalt Congress 2025 runs from 14-15 May in Singapore. The conversation just got a lot more interesting.

For editorial comments or questions: [email protected]